[ w a t e r ]

by Morné Visagie

AKAA, Paris

October 2025

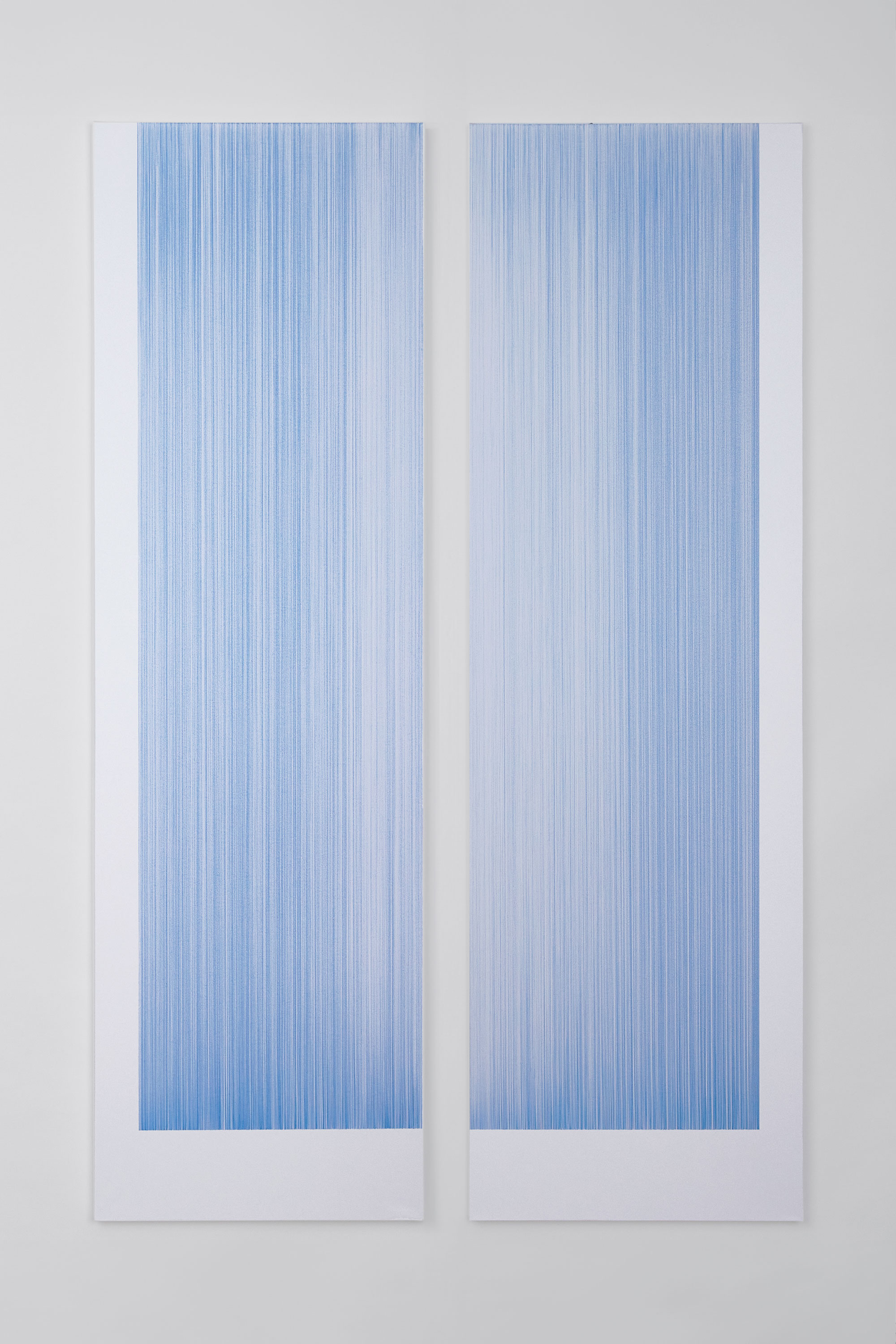

Slow blue love, of Delphinium days II

2025

Pencil on stretched paper

200 x 60 cm (per panel)

To join the river of hours, the sea of years

and the timeless ocean II

2025

Pencil on stretched paper

96 x 60 cm (per panel)

Tossed by the mournful winds,

of the deep II

2025

Pencil on stretched paper

200 x 60 cm

you must hear me I

2025

Drypoint engraving on brass

64 x 40 cm

you must hear me II

2025

Drypoint engraving on brass

64 x 40 cm

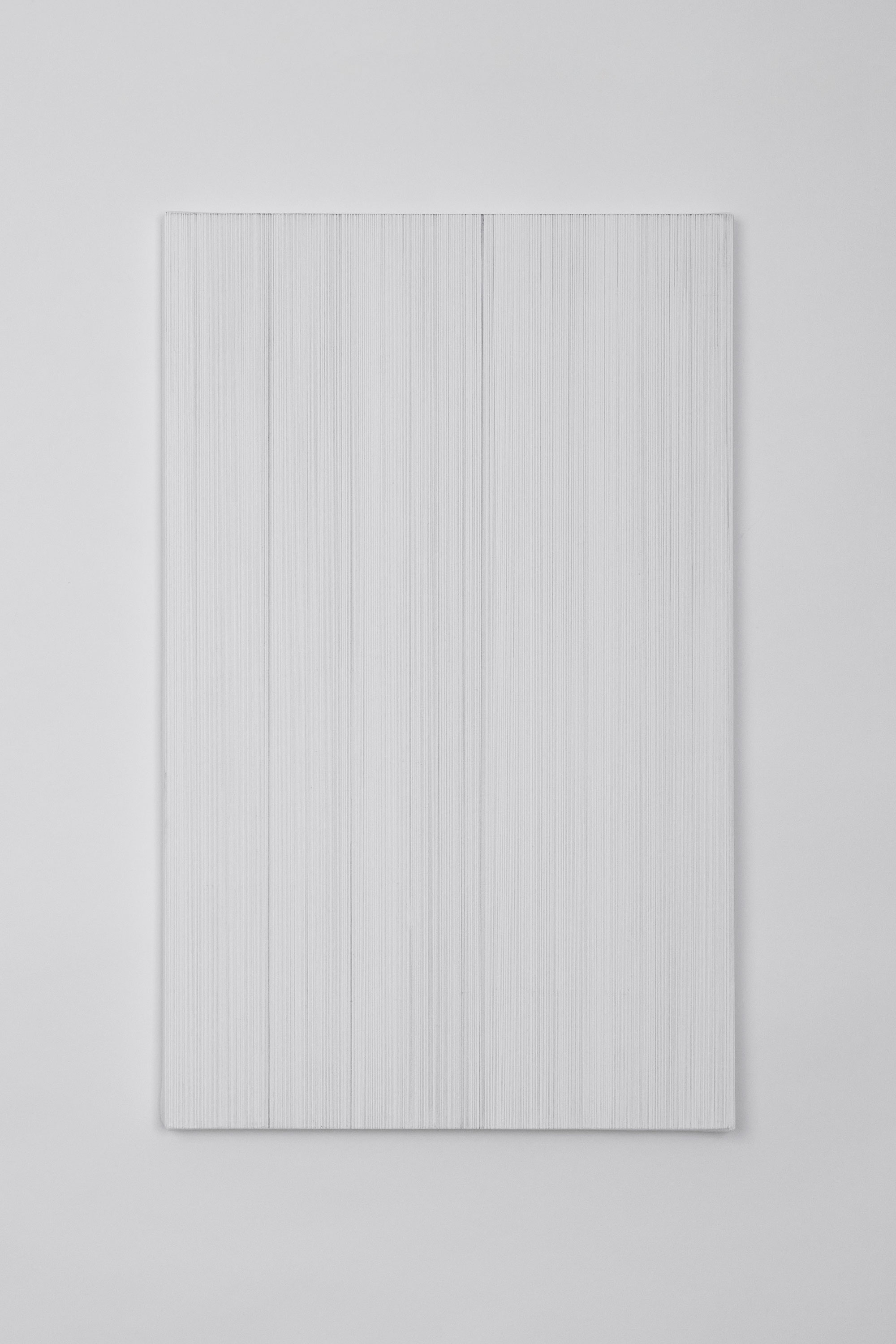

For our time is the passing of a shadow II

2025

Pencil on Italian cotton

96 x 60 cm

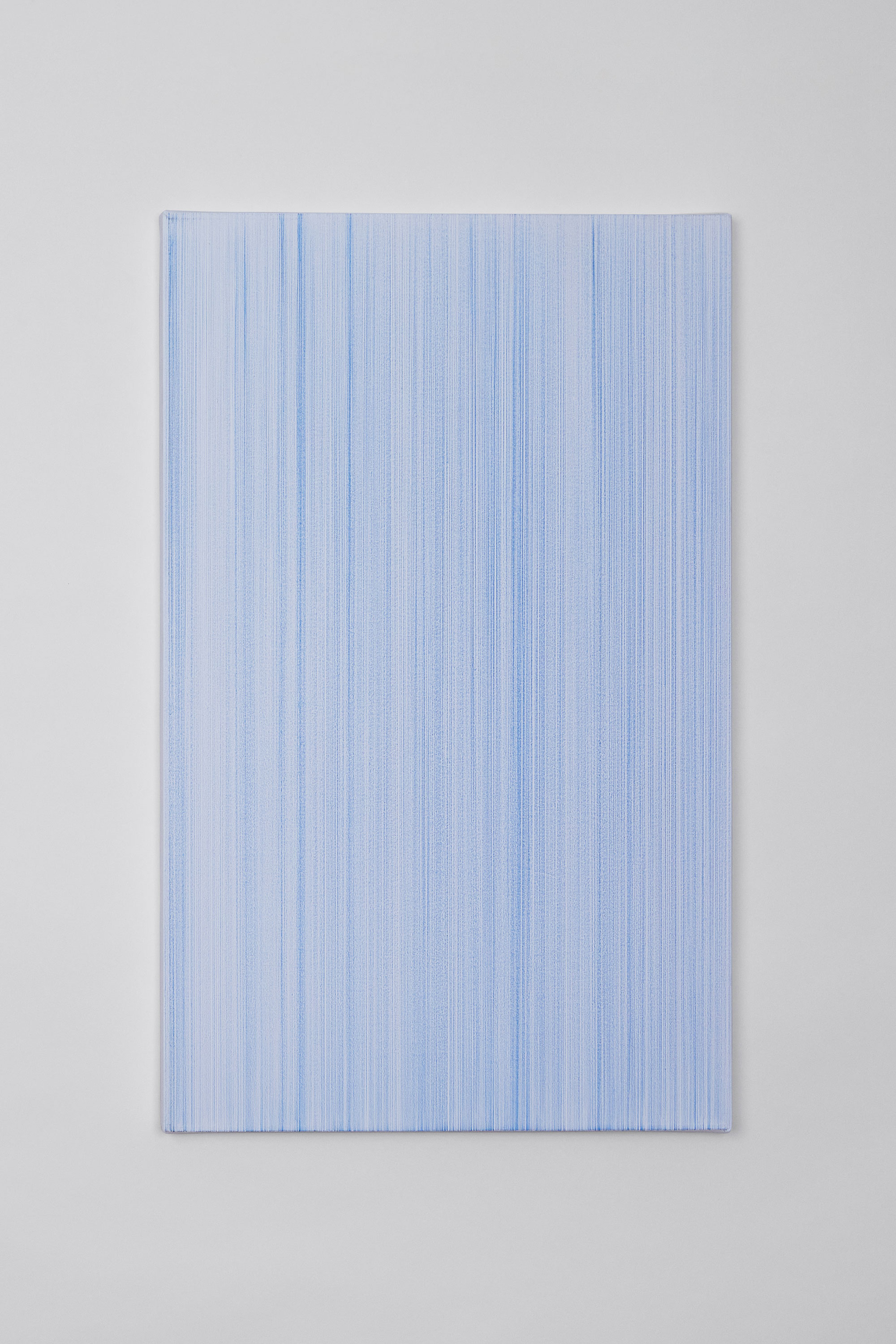

Blue stretches, yawns and is awake II

2025

Pencil on Italian cotton

96 x 60 cm

In the smoking chaos, our shoulder blades touched

(I found you)

2025

Pencil on stretched paper

96 x 60 cm

the truth was

the ships sailed

the rains came

the loss arose

2025

Pencil on stretched paper

96 x 60 cm

Halcyon days of youth II

2025

Drypoint engraving on brass

40 x 25 cm

of

sea and

perils

of water

2025

Drypoint engraving on brass

40 x 25 cm

scattered like mist

that is chased by the rays of the sun I

2025

Drypoint engraving on brass

40 x 25 cm

scattered like mist

that is chased by the rays of the sun II

2025

Drypoint engraving on brass

40 x 25 cm

there is no evidence

in the against of winds

in the consequence of currents

I

2025

Pencil on Italian cotton

60 x 37.5 cm

there is no evidence

in the against of winds

in the consequence of currents

II

2025

Pencil on Italian cotton

60 x 37.5 cm

there is no evidence

in the against of winds

in the consequence of currents

III

2025

Pencil on Italian cotton

60 x 37.5 cm

there is no evidence

in the against of winds

in the consequence of currents

IV

2025

Pencil on Italian cotton

60 x 37.5 cm

the after rains

2025

Pencil on stretched paper

60 x 37.5 cm

Slow blue love, of Delphinium days

(Fragment II)

2025

Pencil on stretched paper

60 x 37.5 cm

To join the river of hours, the sea of years

and the timeless ocean (Fragment I)

2025

Pencil on stretched paper

60 x 37.5 cm

To join the river of hours, the sea of years

and the timeless ocean (Fragment II)

2025

Pencil on stretched paper

60 x 37.5 cm

Tossed by the mournful winds, of the deep (Fragment I)

2025

Pencil on stretched paper

60 x 37.5 cm

Tossed by the mournful winds, of the deep (Fragment II)

2025

Pencil on stretched paper

60 x 37.5 cm

After tomorrow at sunrise

2025

Pencil on stretched paper

37.5 x 60 cm

Our entrance to the past is through memory – either oral or written. And water. In this case saltwater. Sea water. And, as the ocean appears to be the same yet is constantly in motion, affected by tidal movements, so too this memory appears stationary yet is shifting always. Repetition drives the event and the memory simultaneously, becoming a haunting, becoming spectral in its nature.

Haunted by ‘generations of skulls and spirits’, I want the bones.

– M NourbeSe Philip, Zong!, 2008

In [ w a t e r ], Morné Visagie returns to the sea. The title of the exhibition recalls the first poem in M NourbeSe Philip’s 2008 collection, Zong!, an elegiac engagement with memory and mourning. Composed as much from absence as from words, the collection takes as its primary source a legal report that recounts the 1781 massacre on the slave ship Zong as it made the trans-Atlantic crossing. During this passage, 150 of 470 enslaved Africans were thrown overboard, so that the ship’s owner might collect insurance on the ‘lost’ cargo, which would prove more profitable than its sale. The story of these deaths by drowning was nowhere else recorded, the tragedy noted only in the subsequent court case regarding the indemnity of property. No mention of murder, no moral outrage, the massacre reduced to a matter of fraud. Philip’s collection, as the poet writes, “bears witness to the ‘resurfacing of the drowned and the oppressed’ and transforms the desiccated, legal report into a cacophony of voices – wails, cries, moans, and shouts that had earlier been banned from the text.” There is silence, too; the broken words in Philip’s poems hang against the expansive white of the page, suspended as dust motes in water.

The sea has long been a leitmotif in Visagie’s practice. While the artist’s preoccupations have since shifted from personal recollections of a childhood spent on a prison island, a single historical incident connected to that place continues to resonate in these new works. Unable to escape its images, he meets it time and again at each new chapter of his making: the sanctioned murder of two prisoners off the coast in Cape Town in the 1730s, killed in punishment for their intimate encounters. “On 19 August 1735,” a historian offers with the sparest of details, “two men had weights tied around their bodies and, somewhere between the Cape and Robben Island, were dropped into the sea to drown.” The lovers were delivered to their watery deaths a half-century before the enslaved were cast from the Zong. The sea is the same sea, the Atlantic Ocean; at once a physical and metaphoric veil of crossing.

Around the tall, upright works in [ w a t e r ], associations gather – of thresholds or doorways, of journeying from one place to another. To Visagie, the restrained simplicity of these rectangular forms holds a memory of diving boards and poolside encounters, and gestures to the motif of water in queer histories. Yet any suggestion of sensuality is shadowed by the works’ implicit invocation of mortality. The phrase ‘walking the plank’, the artist suggests, offers a dark antonym to the diving board. That each of these works measures his own proportions cannot but recall the stone slabs on which the dead are laid, or those that press down on graves.

“What is the word for bringing bodies back from water? From a ‘liquid grave’?” Philip asks. Finding none, she wonders: “Does this mean that unlike being interred, once you’re underwater there is no retrieval – that you can never [be] ‘exhumed’ from water? The gravestone or tombstone marks the spot of interment, whether of ashes or the body. What marks the spot of subaquatic death?” Reading this passage in Zong!, Visagie was reminded of another by John Berger, which has been something of a touchstone to the artist over the past decade:

What reconciles me to my own death more than anything else is the image of a place: a place where your bones and mine are buried, thrown, uncovered, together. They are strewn there pell-mell. One of your ribs leans against my skull. A metacarpal of my left hand lies inside your pelvis. (Against my broken ribs your breast like a flower.) The hundred bones of our feet are scattered like gravel. It is strange that this image of our proximity, concerning as it does mere phosphate of calcium, should bestow a sense of peace. Yet it does. With you I can imagine a place where to be phosphate of calcium is enough.

This was not the fate of the 150 unnamed Africans on board the Zong. Nor those that survived the massacre. They could not envision a place where they would be buried beside their loved ones. This exquisite loss, which extends even to death, is given material expression in Visagie’s Slow blue love, of Delphinium days, the unity of the work cleaved in two; the two halves unable to be reconciled. The title of the work is taken from Derek Jarman’s Blue(1993), a filmic meditation on colour, blindness, and the illness to which he would slowly succumb. Jarman is a recurring figure throughout Visagie’s work and writing; the artist returns often to his images and words, to Blue and to his journal entries. Both offer insight into the last years of Jarman’s life spent living by the sea, as he witnessed so many friends die of AIDS, watching his own ending rehearsed time and again.

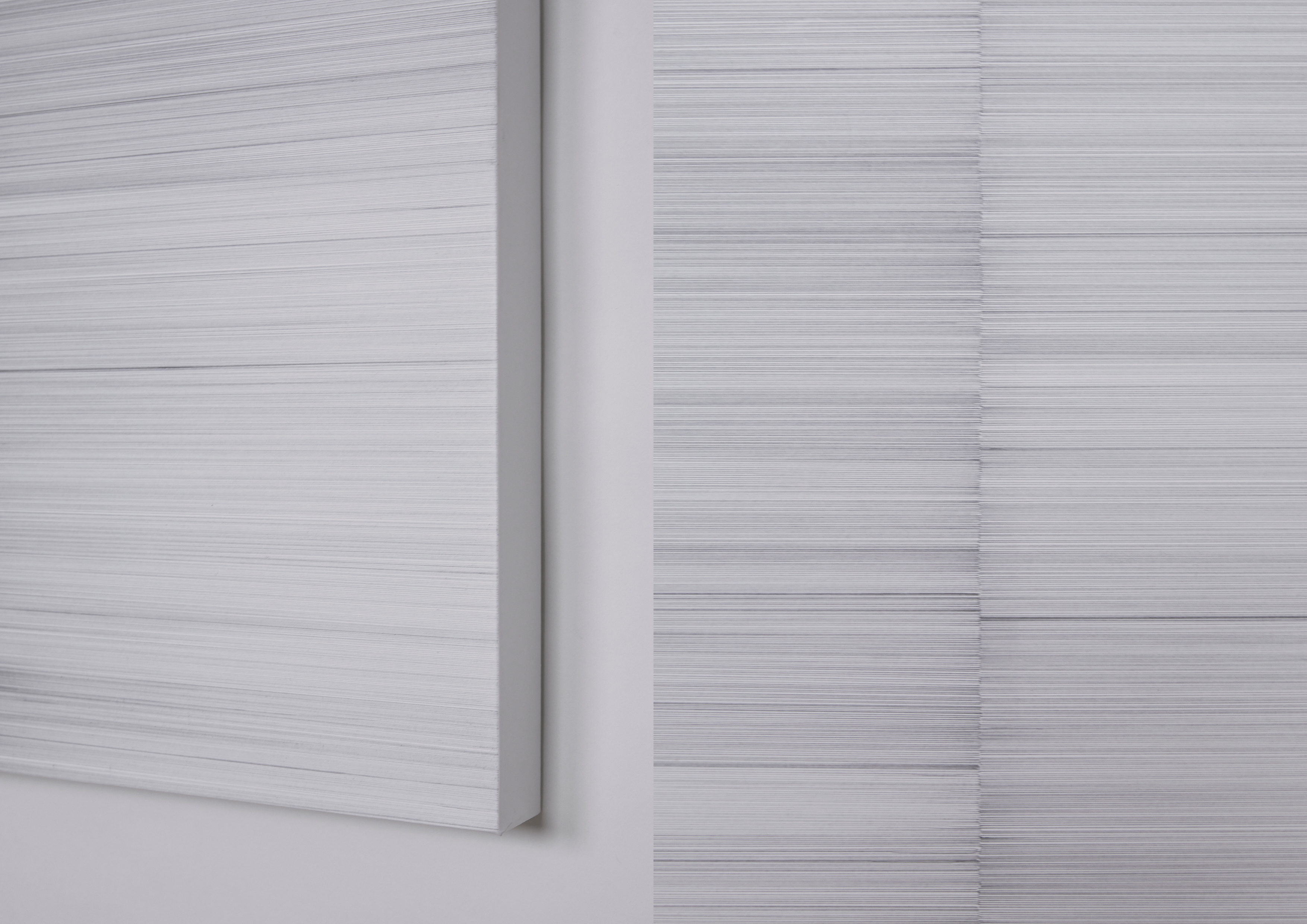

The works in this exhibition are disarmingly understated in their composition: an accumulation of parallel lines on stretched paper, cotton or brass. With only a pencil, needle, and ruler, Visagie meticulously measures and draws line after line across the substrate. Each is witnessed as it is inscribed, the artist attentive to any irregularities: those moments where the sharp lead of the pencil breaks, where the line fades out or is interrupted, where it needs to be reinforced. These areas appear darker, refusing the artist’s ambitions to create a uniform surface. The tone of each line is determined by the weight of the holding hand. With control, the lines are thin and light, but as the hand grows weary, they become heavy, the artist’s fatigue indirectly expressed in the inconstancy of marks.

For Visagie, the seeming simplicity of drawing these lines is fraught with failure. A certain distress is present in these works, in the imperfections that frustrate his ambitions. He must keep the stretched white cotton and paper clean, free from marks or indentations (hours spent drawing lines are irrevocably ruined by a dropped pencil or ruler). He must keep the polished brass from tarnishing, breathing away from it as he works. In these engravings, each needle-fine line is necessarily accompanied by burrs, burrs that would hold ink should the plates be inked up, and once printed would give a softness around the printed marks. Yet left uninked and unprinted, the plates keep their silence. The artist is reminded of the sole narrative of the Zong massacre – that single record of property. What of the names of the enslaved individuals? Only the dead remember them.

For Visagie, process-oriented abstraction allows him to evoke such complexities without assuming the weight of the realities that haunt them. He turns again to Philip, who writes of her collected poems: “The ones I like best are those where the poem escapes the net of complete understanding – where the poem is shot through with glimmers of meaning.” Similarly, an open-endedness of interpretation and a hesitancy to overdetermine characterise Visagie’s practice. Any allusions to historical narratives, literary quotations or art references are transfigured in works of restrained beauty and formal exactitude. Like Philip, Visagie resists comprehension. “I fight the desire to impose meaning on the words,” the poet writes. She continues:

How did they – the Africans on board the Zong – make meaning of what was happening to them? What meaning did they make of it and how did they make it mean?

This story that must be told; that can only be told by not telling.

The smaller works included in [ w a t e r ] appear as fragments from larger compositions. Intimate in scale, seemingly fractured, and separated by emptiness, they are reminiscent of Philip’s poems against the page. As she suggests, “the fragment appears more precious, more beautiful than the whole, if only for its brokenness.” There is something provisional to these scattered words and phrases, a sense shared by Visagie’s works – the impossibility, perhaps, of permanence. What remains in the artist’s line and poet’s word is not certainty, but attention: to the weight of history, to the pull of the sea. Neither seeks resolution, but simply ask that we look, and in looking, remember. Visagie and Philip do not tell a story; they cannot. Instead, they trace its absences, its silences, its hauntings. It is in the space between lines, in the distance between canvases, in the unspoken words, that meaning might surface. The past is not concluded but emergent.

The first poem in Zong!submerges the reader in water – that mercurial medium that, as Philip writes, holds memory but refuses permanence. In Visagie’s work, the viewer is similarly immersed in brine. To artist and poet alike, the sea is both archive and erasure, a site of secrets, of forgetting and remembering. Beneath its metallic mirror, restless currents and silence coincide. [ w a t e r ] offers a material expression of this oceanic tension. However abstract, the works that comprise this exhibition are quietly evocative of bodies of water and the body in water – swimming, sinking, held in stillness.

Edited by Lucienne Bestall